No woman in Greek mythology is more renown than Medea. And perhaps no woman in Greek mythology has a more complete life cycle. Her story begins as an adolescent girl in Colchis at the eastern edge of the Black Sea, passes through two marriages, and continues to maturity as an independent woman with children. Her roles include helper-maiden, a woman who leaves her father for love, wife, mother, and a woman who chooses not to remarry. Despite her foreign status, she holds power as queen in Iolcus and Athens and as primary ruler of Corinth. Her descent from Helios provides her with divine lineage, her association with Hecate and Hera tie her to magic, rejuvenation, and reproduction. Indeed, it is likely that her appeal is rooted in how she crosses boundaries.

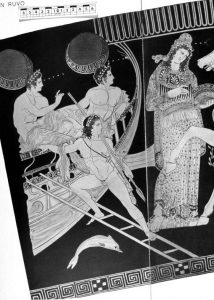

Medea’s mythic biography moves across the known Greek world in a circle, tracing different stages in a woman’s life. Each author who writes of Medea focuses on one part of the story but, often alludes to other phases of her life. When Jason and the Argonauts first come to Colchis at the edge of the known world, Medea is a parthenos, a young unmarried woman, the daughter of King Aeetes. Jason is traveling to fulfill a task given to him by his uncle Pelias to obtain the golden fleece, now hanging in the grove of Ares guarded by a fierce dragon. Through the gods’ intervention, Medea falls in love (Pindar, Pythian 4; Apollonius, Argonautica 3.275-98), and takes the initiative to help Jason by offering him a salve to protect him as he yokes fire-breathing bulls and sows a field with dragon’s teeth (Ap. 3.1013- 62). When Jason must then snatch the golden fleece from the dragon who never sleeps, she drugs the dragon (Ap. 4.123-66) or offers Jason a sleeping potion to render the dragon innocuous. Now that she has betrayed her father twice, she demands that Jason fulfill his promise to take her to Greece and marry him (Ap. 4.345-393). As they escape, they must evade Aeetes’s ships, chasing them in hot pursuit. And so Medea lures her half-brother Apsyrtus into an ambush, where he is murdered by Jason.

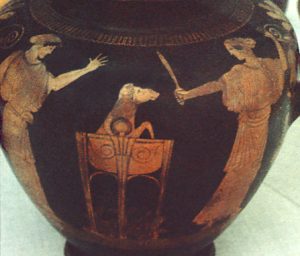

The second phase of her story takes place in Thessaly (central Greece) in the city of Iolcus, where Jason’s uncle Pelias has usurped the throne from Jason’s father, Aeson. There Medea helps Jason take vengeance on his uncle. Approaching Pelias’ daughters, Medea informs them that she has the power to rejuvenate an old ram. After cutting up the ram and adding some herbs, the ram emerges from the cauldron a young, supple animal. The daughters of Pelias are so impressed that they ask Medea to perform the same ritual to make their father young again. Medea gets as far as cutting up Pelias and putting him the boiling cauldron, but does not complete the rest of the ritual. Enraged, Pelias’ daughters chase Medea and Jason out of Iolcus.

Berlin, Pergamon Museum. Photo by Barbara McManus, 1992

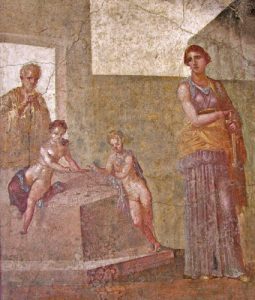

Medea and Jason escape to Corinth, home of the third phase of Medea’s mythic biography. Here competing accounts differ in details. Early accounts by the poets Eumelus (cited in Pausanias 2.3.10) and Simonides (fr. 545) affirm that Medea was queen in Corinth while Euripides’ famous tragedy indicates that both Jason and Medea are essentially refugees, dependent upon the grace and hospitality of the king Creon. When Jason resolves to marry the king’s daughter in order to legitimize their place in Corinth, Euripides’ tragedy depicts Medea responding to his betrayal with vengeance. She sends her children to the bride with a wedding gift, a poison robe. The fatal gift causes the bride’s demise when she puts it on, and her father Creon dies attempting to embrace her. After destroying Jason’s new bride and father-in-law, Medea, according to Euripides, although torn whether to murder her children, ultimately decides to do so to keep Jason’s family line from continuing.

In phase four, Medea accepts Aegeus’ offer of hospitality and flees to Athens. Medea marries Aegeus since he believes he is childless. When Aegeus’ son from his union with Aethra, Theseus, arrives from Troezen, Medea persuades Aegeus to poison the stranger, but Aegeus recognizes his son and knocks the lethal cup from Theseus’ hands at the last second (Bacchylides fr. 18 (Campbell); Callimachus Hecale; Plutarch, Life of Theseus 12.3-7).

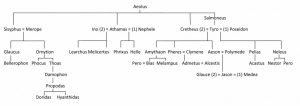

Finally, Medea takes flight to the east to a land called Aria. Her son, named either Medeus or Medus, becomes the eponymous founder of the Medes. Some sources indicate that Jason is the father (Hesiod, Theogony 922-1022) while others claim Aegeus is the father (Herodotus 7.6.2; Strabo 11.526; Pausanias 2.3.8). Typically, when a hero is born who will found a new nation, one parent is divine, such as Zeus and Antiope giving birth to Zethus and Amphion, the founders of Thebes, the union of Poseidon and Melanippe producing Boeotus and Aeolus, the eponymous heroes of Boeotia and Aeolia, or Zeus and Callisto the parents of Arcas, the founder of Arcadia. In this story, Medeus/Medus is the equivalent of these eponymous founders, yet the fact that neither Jason nor Aegeus is divine suggests that she, in fact, is the divine parent. Indeed, the version in Herodotus and Pausanias makes Medea, not her son, the eponymous founder (Krevans 74-76).

At every stage of her life journey, Medea represents another phase in the life of a woman and another aspect of a Greek woman. In Colchis, she is the young unmarried girl (παρθένος) who falls in love, abandons her natal family, and marries a stranger. In Iolcus, she is the new bride (νύμφη) who brings new customs to Jason’s family and fails to be integrated into the new household and community. In Corinth, she is the wife (γυνή) and mother (μήτηρ) who is cut off from her husband Jason. In Athens, she is the new wife, the stepmother (μητρυιά) who wants to protect and promote her child Medeus. Finally, she is a woman who no longer needs a husband, traveling to a new land. Here she names a nation after her own child and acts as an autonomous, independent woman.

Second, at each stage, Medea signifies “foreignness.” As Fritz Graf notes, Medea “is a foreigner, who lives outside of the known world or comes to a city from outside; each time she enters a city where she dwells, she comes from a distant place, and when she leaves that city, she again goes to a distant place” (38). Medea’s combination of autonomy and foreignness poses a threat to the patriarchal hierarchy in Greek society. Can this strong, assertive outsider be trusted? It is no surprise that her autonomy and foreignness is interpreted as having magical or even divine powers, such as when she offers the salve as protection against the fire-breathing bulls or rejuvenates the ram. Interestingly, one author argues that Medea is never punished for her deeds. Is banishment and exile her punishment? Why does she seem to escape every situation with impunity?

Pausanias’ take on Medea

As different authors write for different audiences and utilize different sources, it is little surprise that Medea’s mythic biography contains variations. Given that Pausanias is writing about Corinth, it is only natural that he focuses on the Corinthian portion of Medea’s life story. Yet interestingly enough, he preserves details that are not always recounted in other versions of the tale: 1) Creon’s daughter is given a name, Glauce, and 2) rather than die in the palace in the arms of her father, she leaps into the fountain in order to relieve the poison from the robe. 3) Medea is not a child-killer. Instead, it is the Corinthians who murder Medea’s children, not Medea herself. 4) In fact, Medea conceals the children in the sanctuary of Hera Acraea in order to make them immortal. Furthermore, 5) Medea was the hereditary ruler at Corinth, summoned when Corinthus turned out to be childless.

There may be several reasons why Pausanias preserves these details about the Medea myth. For one, Susan Alcock and others note that Greeks in the Hellenistic world were active not only in restoring old monuments, but also connecting them to local myths and legends. Betsy Robinson posits that the Corinthians of the new Roman colony at Corinth themselves might have participated in this process of “historiating” older monuments such as the Fountain of Glauce, attaching a well-known story to the newly refurbished fountain. As Robinson explains, “on inheriting this monument, Corinth’s rebuilders selected it to become another place where fragments of Corinthian history could be localized in the new urban landscape, and thereby be incorporated within the collective imagination of the new city: (133- 34).

As for Medea and her children, the cult of Hera Acraea, located at Perachora, the “land across,” i.e., the promontory jutting out into the Gulf of Corinth just north of the isthmus, helped protect mothers in pregnancy and the children who might die in the first years of life. According to the archaic poet Eumelus, Medea brings her children to the sanctuary in order to hide them and make them immortal (Paus. 2.3.11), much like Demeter attempts to immortalize Demophon at Eleusis. Jason sees her performing this ritual and misinterprets it as deadly. Yet, the only reason Eumelus offers for the children’s death is Hera’s refusal to protect them. Pausanias (2.3.6-7) reports that the Corinthians respond to the death of Medea’s children in two complementary ways: they erected a δεῖμα “terror” and sent a yearly offering of seven girls and seven boys (Schol. Eur. Med. 264) in an effort to ward off the same deadly end to their own children. As Sarah Iles Johnston explains, “The children’s black clothing suggest that during their year of service, they were temporarily “dead,” having been “sacrificed” to Hera to appease her and thus dissuade her from seizing the children of the Corinthians more widely and permanently. The two techniques—averting apotropaion and appeasing dedication of children—worked toward the same end.” Indeed, another story of Eumelus is recorded, saying that Medea averts a famine in Corinth by sacrificing to Demeter and the Lemnian Nymphs (Schol. Pindar Ol. 13.74).

Finally, why is Medea included in the list of Corinthian rulers and who is Pausanias’ source for this list? In2.3.10, Pausanias identifies his source as the archaic poet Eumelus, who is attempting to make sense of and provide a framework for the many stories of important mythological figures and stories connected with Corinth. The return of the sons of Heracles is traditionally associated with the arrival of the Dorians (1.44.10), and other figures such as Helius, Sisyphus, and Medea are equally notable. Helius was assigned Acrocorinth by the Titan Briareos and had altars there (2.4.6; cf.2.1.6); Homer mentions Sisyphus as King of Ephyra inIliad6.152,210, and Pausanias reports that he rescued Melicertes, helped establish the Isthmian Games, and was buried on the isthmus (2.1.3;2.2.2); and Medea and her children were central to the cult of Hera Acraea (2.3.6, 11). Second, Eumelus is trying to establish a royal pedigree for his patrons the Bacchiad kings that rivals the king lists of Argos and Sparta. By showing that Helius, Medea, Sisyphus, and the sons of Heracles are divine and heroic predecessors, Eumelus provides the Bacchiad kings with a long and venerable line of ancient rulers that validate their right to rule. Moreover, if the chest of Cypselus was dedicated at Olympia by the Bacchiads’ successor, then it suggests that Cypselus included a scene of Medea and Jason on the chest to reinforce his right to rule. Pausanias records that the chest depicts Medea sitting on a throne with Jason and Aphrodite standing on either side (5.18.3). Medea’s rule at Corinth is hereditary through her father Aeetes. Medea, as the daughter of Aeetes, inherited the kingdom after Corinthus died childless. When Medea lost her children, she passed on the kingdom to Sisyphus and his sons. In short, Medea becomes the linchpin that makes possible the orderly succession of rulers from Helius to Sisyphus.

In Pausanias’ versions of Medea’s life story, we can recognize several elements in Pausanias’ way of selecting and organizing his material. First, his tales (logoi) are rooted in the monuments and sights (theoremata) on the ground. The fountain Glauce is named for Creon’s daughter and the memorial to Medea's children is still visible near the Odeum. Second, Pausanias relies on his sources, both literary texts and local guides. Thus, he relies on local guides (and perhaps local records) to explain the traditions behind these same sites and present the site as the Corinthians remembered it. Finally, when confronted with a seemingly disconnected king list, Pausanias (or a predecessor) uses his intellect to stitch together a plausible chronological order to make the list of rulers more coherent. In short, rather than follow the more canonical Euripidean tradition, Pausanias the pepaideumenos reveals both his learning and his respect for the local traditions of ancient Corinth.

Works Cited

Alcock, Susan. “The Heroic Past in a Hellenistic Present.” Hellenistic Constructs. Ed. P. Cartledge, P. Garnsey, and E. Gruen. Berkeley: California, 1997. 20-34.

Graf, Fritz. “Medea, the Enchantress from Afar: Remarks on a Well-Known Myth.” Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art. Ed. James J. Clauss and Sarah Iles Johnston. Princeton: Princeton, 1997. 21-43.

Griffiths, Emma. Medea. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

Johnston, Sarah Iles. “Corinthian Medea and the Cult of Hera Akraia.” Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art. Ed. James J. Clauss and Sarah Iles Johnston. Princeton: Princeton, 1997. 44-70.

Krevans, Nita. “Medea as Foundation-Heroine.” Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art. Ed. James J. Clauss and Sarah Iles Johnston. Princeton: Princeton, 1997. 71-82.

Robinson, Betsy. “Fountains and the Formation of Cultural Identity at Roman Corinth.” Urban Religion in Roman Corinth. Ed. Daniel N. Schowalter and Steven J. Friesen. Cambridge: Harvard, 2005. 111-40.

(Image from banner: Medea rides a chariot pulled by dragons. Lucanian Calyx-Krater, c. 400 BC, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1991.1.)