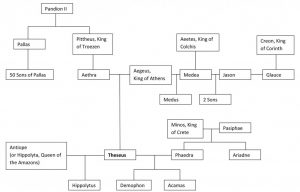

“Loose not the wine-skin’s jutting neck, great chief of the people, until you have returned to the people of Athens” (Plutarch, Life of Theseus 3.3). These cryptic words by the Delphic oracle left Aegeus, king of Athens, perplexed. Little did he realize that the oracle’s words meant that he should not father any children until he returned to Athens. Pittheus, king of Troezen, however, understood the message and used this opportunity to trick Aegeus into sleeping with his daughter Aethra (Thes. 3.1-4). The union Aegeus and Aethra led to the birth of Athens’ greatest hero, Theseus.

Roman, first century BCE – first century CE. From Cerveteri. London, British Museum. Photo by Barbara McManus, 1999

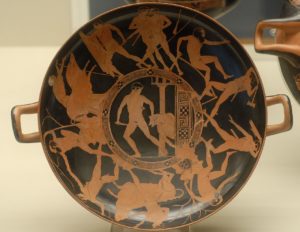

Aegeus’ brother, Pallas, had many sons and Aegeus suspected they were plotting against him on account of his childlessness. Aegeus, in fear of the sons of Pallas, kept his encounter with Aethra secret (Thes. 3.5). In case Aethra bore a child, Aegeus left a pair of boots and a sword under a rock as tokens of his noble birth. Theseus was raised by Aethra in Troezen; once he was old enough to move the stone, Theseus claimed the items which represented his birthright (Paus 1.27.8, Thes. 7.1, 4.1). However, Theseus wanted his actions, not these tokens, to prove his nobility. He felt that taking a simple voyage by boat to meet his father was behavior suitable for a fugitive, so instead he set out on foot for Athens from Troezen, determined to wrong no one, but to punish violent men (Thes. 7.1). Along the way, he preformed six labors emulating the high achievements of the great Hercules (Diodorus Siculus 4.59.1; Thes. 11.1).

While in Epidaurus Theseus first wrestled and slew Periphetes, the son of Hephaestus and Anticlia (APB 3.16.1). Periphetes was also known as Corynetes (Club Man) since he carried a massive club which he used to kill passers-by (Diodorus 4.59.2). Theseus claimed this club, and carried it with him in a similar fashion as his precursor Hercules did with the skin of the Nemean Lion (Thes. 8.1).

At the Isthmus of Corinth Theseus killed Sinis, son of Polypemon and Sylea (Library 3.16.2). Sinis bound his victim’s arms between two bent pine trees, and then quickly released the pines; the resulting force caused his victims to be torn asunder (Diodorus 4.59.3, Paus. 2.1.4). Sinis was slain by Theseus in this same manner (Paus. 2.1.4).

Next Theseus killed Phaea the wild boar near a village called Crommyon between the Isthmus of Corinth and Megarid (Library, Epitome 1.1). Theseus slew the sow so that he could be said to have risked his life in battle with the nobler beasts, instead of just attacking villainous men out of self defense (Thes. 9.1).

At the Cliffs of Sciron (the Molourian rock), Theseus met none other than Sciron himself. Sciron forced passers-by to wash his feet and then kicked his victims into the sea; a giant turtle would then seize them, resulting in their untimely demise (Thes. 10.1-3; Epitome 1.3). Theseus grabbed Sciron by the feet and hurled him into the sea as punishment for his wicked deeds (Epitome 1.3).

In Eleusis Theseus slew Cercyon, son of Branchus and the nymph Argiope (Epitome 1.3). Cercyon wrestled all the passers-by against their will and killed everyone he defeated; only Theseus was skilled enough to defeat Cercyon, and he did so by raising him high and dashing him to the ground (Paus. 1.39.3).

Theseus’ final labor was to slay Procrustes, who is also known as Damastes or Polypemon (Epitome 1.4). Procrustes forced travelers to lie down on his bed and he sawed off parts of their body or stretched their legs until they fit the bed properly (Diodorus 4.59.5). Theseus gave Procrustes the same fate that he had given to so many strangers (Thes. 11.1).

While Theseus journeyed towards Athens, public affairs were full of confusion and dissension, and the private affairs of Aegeus were in a distressing condition. Medea, a sorceress from Colchis, chanced upon Aegeus and promised him that she would use her magic to relieve Aegeus’ childlessness; in return Aegeus swore that Medea would be protected by him and that she would always have a place in his land (Eur. Med. 663-758). Medea had recently fled to Athens from Corinth. Jason, her husband, had remarried Glauce, daughter of King Creon of Corinth in order to increase his own political station. In an act of vengeance Medea killed both Jason’s children and Glauce (Library 1.9.28). After arriving in Athens, Medea married Aegeus and bore a son, Medus (Library 1.9.29).

Theseus did not receive a warm welcome when he reached Athens (Thes. 12.1-3). Medea recognized Theseus’ identity, while Aegeus was ignorant. Fearing that Theseus’ presence would cause Medus not to inherit the throne, she suggested that Aegeus entertain Theseus as guest, and then poison him so that Aegeus would not be threatened by this glorious youth. Since Aegeus was constantly afraid of the sons of Pallas and his private life was in such a disorganized state, he readily agreed to this scheme. During dinner, Theseus drew his sword to cut his meat, revealing his true identity to his father. Aegeus immediately knocked over the cup of poison and formally recognized his son before an assembly.

Theseus did not remain idle, but desiring to do good for his people, he continued to perform great deeds. Theseus went out to tame the Marathonian bull, which had been causing great mischief to the inhabitants of Tetrapolis. Once he mastered the bull, he drove it alive through the city and sacrificed it to Apollo (Thes. 14.1).

Theseus’ next exploit was to slay the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull hybrid, in the Labyrinth at Crete (Thes. 14.2). Androgeos, son of the Cretan king Minos, was killed tragically while in Attica; war ensued and peace was obtained only when Aegeus promised to send a tribute of seven young men and seven young women to Crete to be devoured by the Minotaur every nine years (Thes. 14.1-2). Theseus offered himself as one of these sacrifices, and took off for Crete with his comrades (Thes. 17.1-2). Theseus was able to slay the Minotaur, and with a string he had been given by Ariadne, daughter of Minos, he escaped safely from the labyrinth (Thes. 19.1).

Unfortunately, Theseus had forgotten one thing: he was supposed to change the black sails of his ship to white as a sign to his father that he was successful (Thes. 17.2, 22.1). Aegeus, in a state of utter despair when he saw the ship, hurled himself into the sea that bears his name, the Aegean (Thes. 22.1). As the new king of Athens, Theseus unified Attica into a single political system and refounded the Isthmian Games (Thes. 24-25).

Theseus later went to the Euxine Sea and waged a campaign against the Amazons with Hercules. Theseus received the Amazon Antiope (or Hippolyta according to Herodotus and other authorities) as spoils of war, and they later had a son, Hippolytus (Thes. 26.1-2, 28.2). Theseus’ campaign resulted in a difficult war with the Amazons within Athens itself; the war continued for three months, at which point Antiope was able to negotiate a peace treaty (Thes. 27.1-4).

Theseus was involved in many other heroic actions, most famous of which is the battle with the centaurs. Theseus was a guest at the wedding of Peirithous and Deidameia; the Lapithae and the centaurs were also present (Thes. 30.3). The centaurs became drunk on wine, and began to lay their lands on the women; Theseus and the Lapithae responded with vengeance by slaying the centaurs and expelling them from the country (Thes. 30.3).

Additional Materials: