[1] Βελλεροφόντης δὲ ὁ Γλαύκου τοῦ Σισύφου, κτείνας ἀκουσίως ἀδελφὸν Δηλιάδην, ὡς δέ τινές φασι Πειρῆνα, ἄλλοι δὲ Ἀλκιμένην, πρὸς Προῖτον ἐλθὼν καθαίρεται. καὶ αὐτοῦ Σθενέβοια ἔρωτα ἴσχει, καὶ προσπέμπει λόγους περὶ συνουσίας. τοῦ δὲ ἀπαρνουμένου, λέγει πρὸς Προῖτον ὅτι Βελλεροφόντης αὐτῇ περὶ φθορᾶς προσεπέμψατο λόγους. Προῖτος δὲ πιστεύσας ἔδωκεν ἐπιστολὰς αὐτῷ πρὸς Ἰοβάτην κομίσαι, ἐν αἷς ἐνεγέγραπτο Βελλεροφόντην ἀποκτεῖναι.

- Map

- Pre Reading

- Post Reading

- Culture Essay

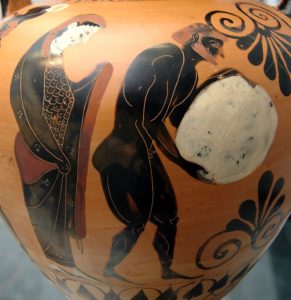

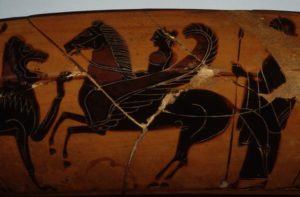

The story of Bellerophon (Library 2.3.1-2)—followed by those of Perseus and Heracles—is the first of successively longer stories told of the great heroes that grew up in the northeastern Peloponnese. Twin brothers, Acrisius and Proetus, link the stories together. When Acrisius drove Proetus from Argos, Proetus sought refuge with Iobates, the king of Lycia in Asia Minor, and married his daughter Sthenoboea. Iobates then helps his son-in-law recover a share of the Argolid and establishes Proetus as king of Tiryns. In response to Sthenoboea’s accusation that Bellerophon attempted to rape her, Proetus sends Bellerophon to Iobates. Acrisius, Proetus’ brother, locked his daughter Danae in a brazen chamber for fear that she would produce a son who would overthrow his father, but she was seduced by Zeus, disguised as a shower of gold, and gave birth to Perseus. Heracles’ mortal father, Amphitryon, is the grandson of Perseus.

Review the Past Tense video. Pay attention to the formation of the passive.

Passive verbs: καθαίρεται, ἐνεγέγραπτο, διαφθαρήσεσθαι, λέγεται, τραφῆναι, γεννηθῆναι, γεγεννημένον, ἀρθείς, μαχεσθῆναι

Why does Proetus send Bellerophon to Iobates rather than punish him for alleged sexual advances toward his wife Sthenoboea?

Say the passage aloud in Greek, but for every pronoun, substitute the appropriate noun to which the pronoun refers.

Apollodorus of Athens was the last in the great tradition of scholars connected with the great Library of Alexandria, Egypt. Born around 180 BCE, he studied under the Stoic Diogenes, moved to Alexandria where he collaborated with Aristarchus, extended Eratosthenes’ Chronicles (Χρονικά) to his death in 120 or 110 BCE, wrote a commentary on Homer’s Catalogue of Ships (Περὶ τοῦ τῶν νεῶν καταλόγου) that offered a geographical account of the Homeric age, and authored an extensive account on Homeric religion called On the Gods (Περὶ θεῶν). In deference to his immense learning, a number of works were later attributed to Apollodorus, most famously the mythological handbook known as the Library (Βιβλιοθήκη). Organized around extended family relationships of the gods and heroes, the Library utilizes these genealogical links to clarify how the vast number of muthoi fit together in a coherent way and to connect various poleis through their divine and heroic family networks. The straightforward storytelling of the Library made it popular as a handbook to students learning Greek myths in antiquity, just as it does today. The last half of Book 3 breaks off after the first two Labors of Theseus and an Epitome provides a shorter account of the last four labors.

The Bibliotheca is an example of a larger genre known as mythography, the collection and organization of mythical stories, often geographically or chronologically. By definition, mythography encompasses a wide range of material, beginning with the Homeric Catalogue of Ships and Hesiod’s Theogony. Mythography is often organized through the use of catalogues, genealogies, theogonies, cosmogonies, and chronological “cycles.” The earliest examples of mythography can be found in the scholia (notes on canonical texts by ancient scholars), the hypotheses (summaries) of tragic drama, or as digressions in geographical or astronomical works, but by the first century BCE, the most common form becomes manuals or handbooks for the reading public, such as the Library. The Library is organized both chronologically and genealogically, beginning with the creation of the cosmos and then by various family trees.