[17] Τοῦτο δὲ παραγγέλλων οὐκ ἐπαινῶ ὅτι οὐκ εἰς τὸ κρεῖσσον ἀλλὰ εἰς τὸ ἧσσον συνέρχεσθε. [18] πρῶτον μὲν γὰρ συνερχομένων ὑμῶν ἐν ἐκκλησίᾳ ἀκούω σχίσματα ἐν ὑμῖν ὑπάρχειν, καὶ μέρος τι πιστεύω. [19] δεῖ γὰρ καὶ αἱρέσεις ἐν ὑμῖν εἶναι: ἵνα [καὶ] οἱ δόκιμοι φανεροὶ γένωνται ἐν ὑμῖν. [20] Συνερχομένων οὖν ὑμῶν ἐπὶ τὸ αὐτὸ οὐκ ἔστιν κυριακὸν δεῖπνον φαγεῖν, [21] ἕκαστος γὰρ τὸ ἴδιον δεῖπνον προλαμβάνει ἐν τῷ φαγεῖν, καὶ ὃς μὲν πεινᾷ, ὃς δὲ μεθύει. [22] μὴ γὰρ οἰκίας οὐκ ἔχετε εἰς τὸ ἐσθίειν καὶ πίνειν; ἢ τῆς ἐκκλησίας τοῦ θεοῦ καταφρονεῖτε, καὶ καταισχύνετε τοὺς μὴ ἔχοντας; τί εἴπω ὑμῖν; ἐπαινέσω ὑμᾶς; ἐν τούτῳ οὐκ ἐπαινῶ.

- Map

- Pre Reading

- Post Reading

- Culture Essay

In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul responds to concerns that the Christian community at Corinth is split into a number of factions. One of the places where this division is most noticeable is at the sacred meal comemmorating Jesus’ last supper with his disciples. As he begins this passage, he notes that the Corinthian Chrstians are coming together not for the better, but for the worse. This is the earliest recorded account of this sacred meal among Christians and Paul makes explicit in verse 23 (παρέλαβον ἀπὸ τοῦ κυρίου ὃ καὶ παρέδωκα ὑμῖν “I received from the Lord what I pass on to you”) that he is passing down the earliest Christian community’s understanding of this meal.

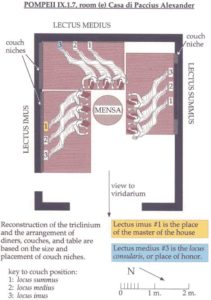

Where did the first Corinthian Christians meet and why might there be divisions among them? It is quite probable that the location for such a communal meal is in the home of a prominent member of the community who had a large enough space to accommodate everyone (e.g., Romans 16:5). Based on Greco-Roman dining practices, banqueters were assigned places of honor according to their social rank and wealth, and even particular dishes and quality of food reinforced social hierarchies and caused divisions among participants. Moreover, “Corinthians and others socialized into hellenistic culture, and with little acquaintance with Jewish scriptures, may well have understood the supper more in terms of Greek memorial feasts for dead heroes” (Horsley, 1 Corinthians, 161).

Review: genitive absolute (Goodell 589–590); purpose clauses, general clauses (Goodell 616)

N/A

Born in Tarsus in Cilicia in the first decade of the common era, Paul (Παῦλος) was raised in a Jewish diaspora community, and as such, found his calling in reaching out to Jewish, urban communities of the eastern Mediterranean. He describes himself as a Jew from birth, “circumcised on the eighth day, of the nation of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew of Hebrews, according to the law, a Pharisee” (Philippians 3:5). He would have learned the Torah and his Jewish faith in the synagogue in Tarsus. At the same time, he would have encountered Hellenistic schooling and philosophy, especially Stoicism, since Tarsus was the home of Athenodorus and other Stoic philosophers.

As a young man, Paul’s devotion to his Jewish faith found expression in persecuting early Christians (Acts 9:1-2, Galatians 1:14), but on the road to Damascus in Syria, he experienced a vision of Christ that caused him to re-evaluate his understanding of his Jewish faith (Acts 9:1-19). Paul described his ministry as the “apostle to the nations,” just as Peter was the “apostle to the circumcised” (Galatians 2:8). After Damascus, his missionary activity took him to Nabatea in Arabia, Jerusalem, Syria and Cilicia (Galatians 1: 17, 18, 21) until he settled in Antioch. He then established church communities in Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Achaea, where he met and worked with Aquila and Prisca in Corinth. Finally, he returned to the coast of Asia Minor where he made Ephesus his home base. After his last visit to Corinth, he intended to return to Jerusalem with funds he had collected to support the church and then set out for Roma and Spain (Romans 15:23-26).

Of the thirteen letters credited to Paul, seven are considered authentic: Romans, first and second Corinthians, Galatians, first Thessalonians, Philippians, and Philemon. Written from 51-56 CE, these letters helped Paul stay in contact with church communities that he had established, respond to specific questions and needs, and settle disputes. Although they include passages of theology and highly rhetorical writing, they are better thought of as letters of friendship rather than formal literary epistles, such as Pliny’s letters. A letter of friendship—in both content and style—is intimate, personal, and familiar, functioning as substitute for the sender’s actual presence. Paul’s letters, moreover, exhibit standard elements of Hellenistic epistolary conventions, including a prescript and thanksgiving, body, and closing exhortation, greetings, and farewell.

Drane, John W. “Paul.” The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Edd. Bruce Metzger and Michael Coogan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Fitzmyer, Joseph, ed. The Acts of the Apostles. The Anchor Bible. New York: Doubleday, 1998.

Fitzmyer, Joseph, ed. First Corinthians. The Anchor Yale Bible. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008.

O’Connor, Jerome Murphy. Paul: A Critical Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.