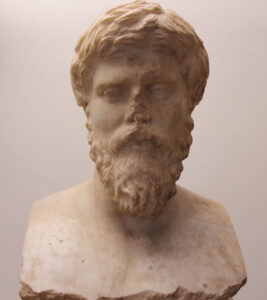

Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, known more commonly as Plutarch, was born and lived most of his life in Chaeronea, a small Boeotian town that split the difference between Athens and Delphi. He acquired a traditional education in rhetoric and then did advanced work in philosophy in Athens. Yet he also developed a keen sense of curiosity and and the active intellectual life through spirited discussions with his family. Many of his dialogues picture Plutarch discussing the questions of the day with his grandfather Lamprias, his father Autobulus, and his brothers Timon and Lamprias. Moreover, his deep appreciation for his wife Timoxena no doubt influenced his thoughts about marriage, women, and sexuality. Beyond his family, his circles of intellectual engagement widened to include hundreds of authors and their books. Without question, Plutarch was a voracious reader. In the Lives alone, Plutarch cites 230 Greek sources and 40 Latin ones (Lamberton 13).

Plutarch’s works can be divided into erga (deeds) and logoi (debates). Yet this simplistic division may hide some deeper truths. Encompassing twenty-one pairs of Greek and Roman biographies, Plutarch’s Lives recount deeds that offer an entrée to ethical character formation (ethopoiia). The prologue to the Life of Pericles (1-2) explains that looking at an action is insufficient; one must subject those actions to contemplation and analysis. And by placing vivid “images of excellence” before the mind’s eye, the recounting of the event evokes an emotional response that makes that deed (and its ethical dimension) all the more memorable (Beck). In short, Plutarch expects his Lives will lead to proper action through emulation.

The other half of Plutarch’s ouevre, misleadingly named the Moralia (Moral Essays), might be better thought of as logoi or arguments, inspired by the discussions he had growing up in Chaeronea. Robert Lamberton divides the Moralia into four major categories. Some of the 80 works that comprise the Moralia are ethical works, such as Tranquillity of Mind and How to Tell a Flatterer from a Friend, and collections of proverbs, such as Sayings of Spartans. Others are polemical in tone and survey the intellectual landscape of the time (e.g., Epicurus makes a Pleasant Life Impossible). Yet many others follow the pattern of “question” (problema) and “cause” (aition), such as Greek Questions and Roman Questions. Finally, following Plato, Plutarch found in dialogues an agreeable model for presenting a polyphony of perspectives and multiple solutions to a given question. Further, like Plato, Plutarch could play with the frame narrative of the dialogue (and consider the contingency of knowledge) and interject myths that explored the questions under discussion in a more imaginative way (Lamberton).

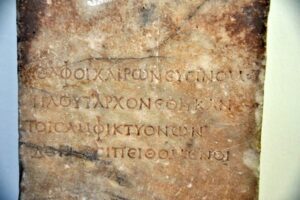

Although it may seem that erga and logoi are at odds with one another, Plutarch believed in an active, engaged life. Homer’s aphorism, “Be a speaker of speeches and a doer of actions,” epitomized his position (Beck). Talented individuals should not rest on the sidelines, but should be active in their community. Thus, Plutarch traveled widely in Greece, Italy, Asia, and Egypt, at times on political missions and at other times delivering speeches in many cities. He was a leader in Chaeronea, an adopted member of the tribe Leontis at Athens, and a priest at Delphi. The emperor Trajan awarded him ornamenta consularia (consular insignia) and Hadrian appointed him procurator of Achaea. In short, Plutarch himself modeled the type of life he expected of others, one that demonstrated both action and contemplation.

Beck, Mark. “Introduction: Plutarch in Greece.” A Companion to Plutarch, ed. by M. Beck. Wiley 2014. 1-9.

Lamberton, Robert. Plutarch. Yale 2001.

Why Study Plutarch and Delphi with Judith Mossman. University of Nottingham. 7 Mar 2016.