[160d] ἔτι δὲ τοῦ Σόλωνος λέγοντος εἰσῆλθε Γόργος ὁ Περιάνδρου ἀδελφός: ἐτύγχανε γὰρ εἰς Ταίναρον ἀπεσταλμένος ἔκ τινων χρησμῶν, τῷ Ποσειδῶνι θυσίαν καὶ θεωρίαν ἀπάγων. ἀσπασαμένων δ᾽ αὐτὸν ἡμῶν καὶ τοῦ Περιάνδρου προσαγαγομένου καὶ φιλήσαντος καθίσας παρ᾽ αὐτὸν ἐπὶ τῆς κλίνης ἀπήγγειλεν ἅττα δὴ πρὸς μόνον ἐκεῖνον, ὁ δ᾽ ἠκροᾶτο, πολλὰ πάσχοντι πρὸς τὸν λόγον ὅμοιος [p. 393] ὤν. τὰ μὲν γὰρ ἀχθόμενος τὰ δ᾽ ἀγανακτῶν ἐφαίνετο, πολλάκις δ᾽ ἀπιστῶν, εἶτα θαυμάζων τέλος δὲ γελάσας πρὸς ἡμᾶς ἔφη . . . [160e] ‘λεκτέον εἰς ἅπαντας, ὦ Γόργε, μᾶλλον δ᾽ ἀκτέον ἐπὶ τοὺς νέους τούτους διθυράμβους ὑπερφθεγγόμενον ὃν ἥκεις λόγον ἡμῖν κομίζων.’

- Map

- Pre Reading

- Post Reading

- Culture Essay

The Story of Arion

Plutarch, Moralia 160d-162b (Symposium of the Seven Sages)

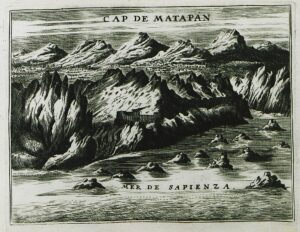

The story of Arion’s voyage to Corinth, imminent death at the hands of the ships’ crew, and subsequent rescue by dolphins is a much beloved and oft repeated tale in antiquity. Although accounts are narrated by Herodotus (1.23-24), Hyginus de Astronomia 2.17, Ovid, Fasti 2.79-128, Lucian, Dialogi Marini 8, and Aulus Gellius (16.19.1-19), Plutarch’s version in the Symposium of the Seven Sages (Septem Sapientium Convivium) has much to recommend it. Its many layered narrative allows the reader to view reactions of audience members, especially Periander the tyrant of Corinth, and of the main character, Arion himself. The narration is told within the frame of the symposium by Plutarch’s narrator Diocles, then by Periander’s brother Gorgus, who then reports in indirect discourse Arion’s account of his rescue. Arion’s journey—from Taras (Tarentum) in southern Italy to Taenarum in the southern Peloponnese (Gardner) and finally to Corinth where Periander rules—anchors the narrative to three sanctuaries of Poseidon.

As the inventor of the dithyramb, a choral hymn in honor of Dionysus, Arion is linked to Dionysus while as kitharode who sings the Pythian hymn, he is linked to Apollo. The Homeric Hymn to Dionysus and the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, moreoever, both feature dolphins, although in different ways: Dionysus transforms the ship’s recalcitrant crew into dolphins while Apollo leapt onto the ship as a dolphin and guided the Cretan crew to Delphi. Finally, the rescue of Arion by dolphins allows Plutarch to expatiate on dolphins’ philanthropia and love of music. In fact, the dolphins’ rescue of Arion recalls more than a dozen stories of human-dolphin interactions, including the dolphin’s rescue of Melicertes-Palaemon after his plunge into the sea with his mother (Csapo; Mossman; Williams).

Works Cited

Csapo, Eric. “The Dolphins of Dionysus.” Poetry, Theory, Praxis.: The Social Life of Myth, Word and Image in Ancient Greece. Essays in Honour of William J. Slater. Ed. by E. Csapo an M. C. Miller. Oxbow Books, 2003. 69-98.

Gardner, Chelsea. “Chelsea Gardner talks about Ancient Tainaron.” Peopling the Past, Video #12, 7 July 2021.

Mossman, Judith. “Plutarch’s Dinner of the Seven Wise Men and its Place in Symposion Literature.” Plutarch and his Intellectual World. Ed. J. Mossman. London and Swansea 1997. 119-140.

Williams, Craig. “When a Dolphin Loves a Boy: Some Greco-Roman and Native American Love Stories.” Classical Antiquity 32.1 (2013) 200-242.

n/a

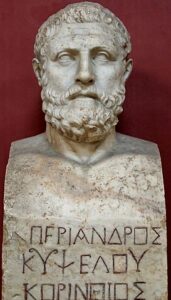

The Tradition of the Seven Sages

The idea of a list of seven extraordinary wise men of Archaic Greece fits a common pattern in Greek thought. Greeks were constantly making lists of inventors and producing catalogs. Besides the Seven Sages, we have, for example, Thespis the inventor of drama, Arion the inventor of the dithyramb, the nine muses, the seven wonders of the ancient world. Many of these emerged after Alexander’s conquests during the Hellenistic period as Greek culture spread and works became canonized. But what made the list of seven sages so potent was the Greek love of gnomai, short proverbs or maxims that packed a powerful punch. These pithy expressions were part of the Greek folk wisdom tradition. Who better to utter these expressions than this group of political leaders and philosophers from the 6th century BCE.

There was just one problem with this group: who belonged to the group was in dispute. Plato in his dialogue Protagoras was the first to list the seven sages as a group: Thales of Miletus, Pittacus of Mytilene, Bias of Priene, Solon of Athens, Cleoboulus of Lindus, Myson of Chenae, and Chilon of Sparta (342e-343b). The first four became canonical, but Diogenes Laertius names sixteen possible candidates for the seven slots (Lendering). Plutarch is well-aware of these disputes and purposely keeps readers of his Symposium of the Seven Sages guessing who the seven are and whether Periander is one of the seven until midway through the dialogue (Stamatopoulou). In fact, one could say that Plutarch purposely expands the pool to include wise men from other cultures (e.g., Anacharsis the Scythian) and different backgrounds (the slave Aesop). And even though the story of Arion is not a maxim, it comes from a folk tradition and has a message, shaped by the eyewitness (re)telling, for both the attendees at the symposium as well as for us.

So what makes a good proverb? In Mabel Lang’s study of gnomic expressions in Herodotus, she concluded “”whether the maxim is used to support a warning, to explain a point being made, or to urge a course of action, it applies a generally accepted truth to the particular situation and so puts it in a context that lends conviction (65). Other scholars note that proverbs are used to “sum up a situation, pass judgment, recommend a course of action, or serve as precedents for present action” (Dundes and Arewa, cited in Shapiro 93). As advice rooted in a cultural tradition, it can serve as a useful way to offer criticism in an indirect way. As part of an oral tradition, the advice depends on the context, and factors such as the age and status and relationship of the speaker to the listener can change its message (Shapiro). In the 5th century CE, Stobaeus (Anth. 3.1.173) reports that 147 maxims were inscribed at Delphi, although not all could be attributed to the seven sages.

Read through the gnomic statements collected by Shapiro and choose three that speak to you and might offer inspiration. After choosing three proverbs, share your picks with others and explain why you chose them. Finally, memorize the three so that you will always have good advice at hand.

Lang, Mabel. Herodotean Narrative and Discourse. Cambridge, MA 1984.

Lendering, Jona. “Seven Sages.” Livius.org 22 Sep 2020. < https://www.livius.org/articles/people/seven-sages/>

Shapiro, Susan. “Proverbial Wisdom in Herodotus.” TAPA 130 (2000) 89-118.

Stamatopoulou, Zoe. “Constructing Periander in Plutarch’s Symposium of the Seven Sages.” CHS Research Bulletin 5.1 (2016).